soul+aspects

OED + Wikipedia

The soul, in many religious, philosophical, and mythologicaltraditions, is theincorporeal essence of a living being.[1] Soul orpsyche (Ancient Greek: ψυχή psykhḗ, of ψύχεινpsýkhein, "to breathe") comprises the mental abilities of a living being: reason, character, feeling, consciousness, memory, perception, thinking, etc. Depending on the philosophical system, a soul can either be mortal or immortal.[2]

Greek philosophers, such as Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle, understood that the soul (ψυχή psūchê) must have a logical faculty, the exercise of which was the most divine of human actions. At his defense trial, Socrates even summarized his teaching as nothing other than an exhortation for his fellow Athenians to excel in matters of the psyche since all bodily goods are dependent on such excellence (Apology30a–b).

In Judaism and in Christianity, only human beings have immortal souls (although immortality is disputed within Judaism and the concept of immortality may have been influenced by Plato).[3] For example, the Catholic theologian Thomas Aquinas attributed "soul" (anima) to all organisms but argued that only human souls are immortal.[4] Other religions (most notably Hinduism and Jainism) hold that all living things from the smallest bacterium to the largest of mammals are the souls themselves (Atman, jiva) and have their physical representative (the body) in the world. The actual self is the soul, while the body is only a mechanism to experience the karma of that life. Thus if we see a tiger then there is a self-conscious identity residing in it (the soul), and a physical representative (the whole body of the tiger, which is observable) in the world. Some teach that even non-biological entities (such as rivers and mountains) possess souls. This belief is calledanimism.[5]

Contents

- 1 Etymology

- 2 Synonyms

- 3 Religious views

- 4 Philosophical views

- 5 Science

- 6 Parapsychology

- 7 See also

- 8 References

- 9 Further reading

- 10 External links

Etymology[edit]

|

This section does not cite anysources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.

Find sources: "Soul" – news · newspapers ·books · scholar · JSTOR (October 2017) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

The Modern English word "soul", derived from Old English sáwol, sáwel, was first attested in the 8th century poem Beowulf v. 2820 and in the Vespasian Psalter 77.50 . It is cognate with other German andBaltic terms for the same idea, including Gothic saiwala, Old High German sêula, sêla, Old Saxon sêola, Old Low Franconian sêla, sîla,Old Norse sála and Lithuanian siela. Deeper etymology of theGermanic word is unclear.

The original concept behind the Germanic root is thought to mean “coming from or belonging to the sea (or lake)”, because of the Germanic and pre-Celtic belief in souls emerging from and returning to sacred lakes, Old Saxon sêola (soul) compared to Old Saxon sêo(sea).

Synonyms[edit]

|

This section does not cite anysources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.

Find sources: "Soul" – news · newspapers ·books · scholar · JSTOR (October 2019) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

The Koine Greek Septuagint uses ψυχή (psyche) to translate Hebrewנפש (nephesh), meaning "life, vital breath", and specifically refers to a mortal, physical life, but in English it is variously translated as "soul, self, life, creature, person, appetite, mind, living being, desire,emotion, passion";[citation needed] an example can be found in Genesis 1:21:

Hebrew – וַיִּבְרָא אֱלֹהִים, אֶת-הַתַּנִּינִם הַגְּדֹלִים; וְאֵת כָּל-נֶפֶשׁ הַחַיָּה הָרֹמֶשֶׂת[citation needed] Septuagint – καὶ ἐποίησεν ὁ θεὸς τὰ κήτη τὰ μεγάλα καὶ πᾶσαν ψυχὴν ζῴων ἑρπετῶν. Vulgate – Creavitque Deus cete grandia, et omnem animam viventem atque motabilem. Authorized King James Version – "And God created great whales, and every living creature that moveth."The Koine Greek word ψυχή (psychē), "life, spirit, consciousness", is derived from a verb meaning "to cool, to blow", and hence refers to the breath, as opposed to σῶμα (soma), meaning "body".[citation needed] Psychē occurs juxtaposed to σῶμα, as seen inMatthew 10:28:

Greek – καὶ μὴ φοβεῖσθε ἀπὸ τῶν ἀποκτεννόντων τὸ σῶμα, τὴν δὲ ψυχὴν μὴ δυναμένων ἀποκτεῖναι· φοβεῖσθε δὲ μᾶλλον τὸν δυνάμενον καὶ ψυχὴν καὶ σῶμα ἀπολέσαι ἐν γεέννῃ. Vulgate – et nolite timere eos qui occidunt corpus animam autem non-possunt occidere sed potius eum timete qui potest et animam et corpus perdere in gehennam. Authorized King James Version (KJV) – "And fear not them which kill the body, but are not able to kill the soul: but rather fear him which is able to destroy both soul and body in hell."Paul the Apostle used ψυχή (psychē) and πνεῦμα (pneuma) specifically to distinguish between the Jewish notions of נפש(nephesh) and רוח ruah (spirit)[citation needed] (also in the Septuagint, e.g. Genesis 1:2 רוּחַ אֱלֹהִים = πνεῦμα θεοῦ = spiritus Dei = "the Spirit of God").

Religious views[edit]

Ancient Near East[edit]

In the ancient Egyptian religion, an individual was believed to be made up of various elements, some physical and some spiritual. Similar ideas are found in ancient Assyrian and Babylonian religion. Kuttamuwa, an 8th-century BCE royal official from Sam'al, ordered an inscribedstele erected upon his death. The inscription requested that his mourners commemorate his life and his afterlifewith feasts "for my soul that is in this stele". It is one of the earliest references to a soul as a separate entity from the body. The 800-pound (360 kg) basalt stele is 3 ft (0.91 m) tall and 2 ft (0.61 m) wide. It was uncovered in the third season of excavations by the Neubauer Expedition of the Oriental Institute in Chicago, Illinois.[6]

Bahá'í[edit]

The Bahá'í Faith affirms that "the soul is a sign of God, a heavenly gem whose reality the most learned of men hath failed to grasp, and whose mystery no mind, however acute, can ever hope to unravel".[7]Bahá'u'lláh stated that the soul not only continues to live after the physical death of the human body, but is, in fact, immortal.[8] Heaven can be seen partly as the soul's state of nearness to God; and hell as a state of remoteness from God. Each state follows as a natural consequence of individual efforts, or the lack thereof, to develop spiritually.[9] Bahá'u'lláh taught that individuals have no existence prior to their life here on earth and the soul's evolution is always towards God and away from the material world.[9]

Buddhism[edit]

Buddhism teaches the principle of impermanence, that all things are in a constant state of flux: all is changing, and no permanent state exists by itself.[10][11] This applies to human beings as much as to anything else in the cosmos. Thus, a human being has no permanent self.[12][13] According to this doctrine of anatta (Pāli; Sanskrit:anātman) – "no-self" or "no soul" – the words "I" or "me" do not refer to any fixed thing. They are simply convenient terms that allow us to refer to an ever-changing entity.[14]

The anatta doctrine is not a kind of materialism. Buddhism does not deny the existence of "immaterial" entities, and it (at least traditionally) distinguishes bodily states from mental states.[15] Thus, the conventional translation of anatta as "no-soul"[16] can be confusing. If the word "soul" simply refers to an incorporeal component in living things that can continue after death, then Buddhism does not deny the existence of the soul.[17] Instead, Buddhism denies the existence of a permanent entity that remains constant behind the changing corporeal and incorporeal components of a living being. Just as the body changes from moment to moment, so thoughts come and go, and there is no permanent state underlying the mind that experiences these thoughts, as in Cartesianism. Conscious mental states simply arise and perish with no "thinker" behind them.[18] When the body dies, Buddhists believe the incorporeal mental processes continue and are reborn in a new body.[17] Because the mental processes are constantly changing, the being that is reborn is neither entirely different from, nor exactly the same as, the being that died.[19] However, the new being iscontinuous with the being that died – in the same way that the "you" of this moment is continuous with the "you" of a moment before, despite the fact that you are constantly changing.[20]

Buddhist teaching holds that a notion of a permanent, abiding self is a delusion that is one of the causes of human conflict on the emotional, social, and political levels.[21][22] They add that an understanding ofanatta provides an accurate description of the human condition, and that this understanding allows us to pacify our mundane desires.

Various schools of Buddhism have differing ideas about what continues after death.[23] The Yogacara school in MahayanaBuddhism said there are Store consciousness which continue to exist after death.[24] In some schools, particularly Tibetan Buddhism, the view is that there are three minds: very subtle mind, which does not disintegrate in death; subtle mind, which disintegrates in death and which is "dreaming mind" or "unconscious mind"; and gross mind, which does not exist when one is sleeping. Therefore, gross mind is less permanent than subtle mind, which does not exist in death. Very subtle mind, however, does continue, and when it "catches on", or coincides with phenomena, again, a new subtle mind emerges, with its own personality/assumptions/habits, and that entity experienceskarma in the current continuum.

Plants were said to be non-sentient (無情),[25] but Buddhist monks are required to not cut or burn trees, because some sentient beings rely on them.[26] Some Mahayana monks said non-sentient beings such as plants and stones have Buddha-nature.[27][28]

Certain modern Buddhists, particularly in Western countries, reject—or at least take an agnostic stance toward—the concept of rebirth or reincarnation. Stephen Batchelor discusses this in his book Buddhism Without Beliefs. Others point to research that has been conducted at the University of Virginia as proof that some people are reborn.[29]

Christianity[edit]

According to a commonChristian eschatology, when people die, their souls will be judged by God and determined to go to Heaven or to Hadesawaiting the resurrection. Other Christians understand the soul as the life, and believe that the dead have no life untilafter the resurrection (Christian conditionalism). Some Christians believe that the souls and bodies of the unrighteous will be destroyed in hell rather than suffering eternally (annihilationism). Believers will inherit eternal life either in Heaven, or in a Kingdom of God on earth, and enjoy eternal fellowship with God.

Although all major branches of Christianity – Catholics, Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, Church of the East, Evangelical, andmainline Protestants – teach that Jesus Christ plays a decisive role in the Christian salvation process, the specifics of that role and the part played by individual persons or by ecclesiastical rituals and relationships, is a matter of wide diversity in official church teaching, theological speculation and popular practice. Some[which?] Christians believe that if one has not repented of one's sins and has not trusted in Jesus Christ as Lord and Savior, one will go to Hell and suffer eternal damnation or eternal separation from God. Some[who?] hold a belief that babies (including the unborn) and those with cognitive or mental impairments who have died will be received into Heaven on the basis of God's grace through the sacrifice of Jesus.[30][need quotation to verify]

There are also beliefs in universal salvation.

Origin of the soul[edit]

The "origin of the soul" has provided a vexing question in Christianity. The major theories put forward include soul creationism,traducianism, and pre-existence. According to soul creationism, God creates each individual soul created directly, either at the moment of conception or some later time. According to traducianism, the soul comes from the parents by natural generation. According to the preexistence theory, the soul exists before the moment of conception. There have been differing thoughts regarding whether human embryos have souls from conception, or whether there is a point between conception and birth where the fetus acquires a soul, consciousness, and/or personhood. Stances in this question might play a role in judgements on themorality of abortion.[31][32][33]

Trichotomy of the soul[edit]

Augustine (354-430), one of western Christianity's most influential early Christian thinkers, described the soul as "a special substance, endowed with reason, adapted to rule the body". Some Christians espouse a trichotomic view of humans, which characterizes humans as consisting of a body (soma), soul (psyche), and spirit (pneuma).[34] However, the majority of modern Bible scholars point out how the concepts of "spirit" and of "soul" are used interchangeably in many biblical passages, and so hold to dichotomy: the view that each human comprises a body and a soul. Paul said that the "body wars against" the soul, "For the word of God is living and active and sharper than any two-edged sword, and piercing as far as the division of soul and spirit" (Heb 4:12 NASB), and that "I buffet my body", to keep it under control.

Views of various denominations[edit]

The present Catechism of the Catholic Church defines the soul as "the innermost aspect of humans, that which is of greatest value in them, that by which they are in God's image described as 'soul' signifies thespiritual principle in man".[35] All souls living and dead will be judged by Jesus Christ when he comes back to earth. The Catholic Church teaches that the existence of each individual soul is dependent wholly upon God: "The doctrine of the faith affirms that the spiritual and immortal soul is created immediately by God."[36]

Protestants generally believe in the soul's existence, but fall into two major camps about what this means in terms of anafterlife. Some, followingCalvin,[37] believe in theimmortality of the soul and conscious existence after death, while others, following Luther,[38]believe in the mortality of the soul and unconscious "sleep" until the resurrection of the dead.[39] Various new religious movements deriving fromAdventism—including Christadelphians,[40] Seventh-day Adventists[citation needed] and Jehovah's Witnesses[41][42]—similarly believe that the dead do not possess a soul separate from the body and are unconscious until the resurrection.

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints teaches that the spirit and body together constitute the Soul of Man (Mankind). "The spirit and the body are the soul of man."[43] Latter-day Saints believe that the soul is the union of a pre-existing, God-made spirit[44][45][46] and a temporal body, which is formed by physical conception on earth. After death, the spirit continues to live and progress in the Spirit world until the resurrection, when it is reunited with the body that once housed it. This reuniting of body and spirit results in a perfect soul that is immortal and eternal and capable of receiving a fulness of joy.[47][48] Latter-day Saint cosmology also describes "intelligences" as the essence of consciousness or agency. These are co-eternal with God, and animate the spirits.[49] The union of a newly-created spirit body with an eternally-existing intelligence constitutes a "spirit birth"[citation needed] and justifies God's title "Father of our spirits".[50][51][52]

Confucianism[edit]

Some Confucian traditions contrast a spiritual soul with a corporeal soul.[53]

Hinduism[edit]

Ātman is a Sanskrit word that means inner self or soul.[54][55][56] In Hindu philosophy, especially in the Vedanta school ofHinduism, Ātman is thefirst principle,[57] the trueself of an individual beyond identification with phenomena, the essence of an individual. In order to attain liberation (moksha), a human being must acquire self-knowledge (atma jnana), which is to realize that one's true self (Ātman) is identical with the transcendent selfBrahman.[55][58]

The six orthodox schools of Hinduism believe that there is Ātman (self, essence) in every being.[59]

In Hinduism and Jainism, a jiva (Sanskrit: जीव, jīva, alternative spellingjiwa; Hindi: जीव, jīv, alternative spelling jeev) is a living being, or any entity imbued with a life force.[60]

In Jainism, jiva is the immortal essence or soul of a living organism (human, animal, fish or plant etc.) which survives physical death.[61]The concept of Ajiva in Jainism means "not soul", and represents matter (including body), time, space, non-motion and motion.[61] In Jainism, a Jiva is either samsari (mundane, caught in cycle of rebirths) or mukta (liberated).[62][63]

The concept of jiva in Jainism is similar to atman in Hinduism. However, some Hindu traditions differentiate between the two concepts, with jiva considered as individual self, while atman as that which is universal unchanging self that is present in all living beings and everything else as the metaphysical Brahman.[64][65][66] The latter is sometimes referred to as jiva-atman (a soul in a living body).[64] According to Brahma Kumaris, the soul is an eternal point of light.

Islam[edit]

The Quran, the holy book of Islam, distinguishes between the immortal Rūḥ (translated as spirit, consciousness, pneuma or "soul") and the mortal Nafs (translated as self, ego, psyche or "soul").[67][68]The immortal Rūḥ "drives" the mortal Nafs, which comprises temporal desires and perceptions necessary for living.[69] One of the passages in the Quran that mention Rûh occur in chapter 17 ("The Night Journey"),and in Chapter 39 ("The Troops"):

Jainism[edit]

In Jainism, every living being, from plant or bacterium to human, has a soul and the concept forms the very basis of Jainism. According to Jainism, there is no beginning or end to the existence of soul. It is eternal in nature and changes its form until it attains liberation.

The soul (Jīva) is basically categorized in one of two ways based on its present state.[citation needed]

- Liberated Souls – These are souls which have attained liberation (moksha) and never become part of the life cycle again.

- Non-Liberated Souls – The souls of any living being which are stuck in the life cycle of 4 forms; Manushya Gati (Human Being), Tiryanch Gati (Any other living being), Dev Gati(Heaven) and Narak Gati (Hell).

Until the time the soul is liberated from the saṃsāra (cycle of repeated birth and death), it gets attached to one of these bodies based on the karma (actions) of the individual soul. Irrespective of which state the soul is in, it has got the same attributes and qualities. The difference between the liberated and non-liberated souls is that the qualities and attributes are manifested completely in case ofsiddha (liberated soul) as they have overcome all the karmic bondages whereas in case of non-liberated souls they are partially exhibited. Souls who rise victorious over wicked emotions while still remaining within physical bodies are referred to as arihants.[70]

Concerning the Jain view of the soul, Virchand Gandhi said

Judaism[edit]

|

This Section relies too much onreferences to primary sources.Please improve this Section by addingsecondary or tertiary sources. (October 2019) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)

|

The Hebrew terms נפש nefesh (literally "living being"), רוח ruach(literally "wind"), נשמה neshamah (literally "breath"), חיה chayah(literally "life") and יחידה yechidah (literally "singularity") are used to describe the soul or spirit.[72]

In Judaism the soul was believed to be given by God to Adam as mentioned in Genesis,

Judaism relates the quality of one's soul to one's performance of the commandments (mitzvot) and reaching higher levels of understanding, and thus closeness to God. A person with such closeness is called a tzadik. Therefore, Judaism embraces the commemoration of the day of one's death, nahala/Yahrtzeit and not the birthday[73] as a festivity of remembrance, for only toward the end of life's struggles, tests and challenges could human souls be judged and credited for righteousness.[74][75] Judaism places great importance on the study of the souls.[76]

Kabbalah and other mystic traditions go into greater detail into the nature of the soul. Kabbalah separates the soul into five elements, corresponding to the five worlds:

- Nefesh, related to natural instinct.

- Ruach, related to emotion and morality.

- Neshamah, related to intellect and the awareness of God.

- Chayah, considered a part of God, as it were.

- Yechidah. This aspect is essentially one with God.

Kabbalah also proposed a concept of reincarnation, the gilgul. (See also nefesh habehamit the "animal soul".)

Scientology[edit]

The Scientology view is that a person does not have a soul, it is a soul. A person is immortal, and may be reincarnated if they wish. The Scientology term for the soul is "thetan", derived from the Greek word "theta", symbolizing thought. Scientology counselling (called auditing) addresses the soul to improve abilities, both worldly and spiritual.

Shamanism[edit]

The belief in soul dualism found throughout most Austronesianshamanistic traditions. The reconstructed Proto-Austronesian word for the "body soul" is *nawa ("breath", "life", or "vital spirit"). It is located somewhere in the abdominal cavity, often in the liver or the heart(Proto-Austronesian *qaCay).[77][78] The "free soul" is located in the head. Its names are usually derived from Proto-Austronesian *qaNiCu("ghost", "spirit [of the dead]"), which also apply to other non-human nature spirits. The "free soul" is also referred to in names that literally mean "twin" or "double", from Proto-Austronesian *duSa("two").[79][80] A virtuous person is said to be one whose souls are in harmony with each other, while an evil person is one whose souls are in conflict.[81]

The "free soul" is said to leave the body and journey to the spirit world during sleep, trance-like states, delirium, insanity, and death. The duality is also seen in the healing traditions of Austronesian shamans, where illnesses are regarded as a "soul loss" and thus to heal the sick, one must "return" the "free soul" (which may have been stolen by an evil spirit or got lost in the spirit world) into the body. If the "free soul" can not be returned, the afflicted person dies or goes permanently insane.[82]

In some ethnic groups, there can also be more than two souls. Like among the Tagbanwa people, where a person is said to have six souls - the "free soul" (which is regarded as the "true" soul) and five secondary souls with various functions.[77]

Kalbo Inuit groups believe that a person has more than one type of soul. One is associated with respiration, the other can accompany the body as a shadow.[83] In some cases, it is connected to shamanistic beliefs among the various Inuit groups.[84] Also Caribou Inuit groups believed in several types of souls.[85]

The shaman heals within the spiritual dimension by returning 'lost' parts of the human soul from wherever they have gone. The shaman also cleanses excess negative energies, which confuse or pollute the soul.

Sikhism[edit]

Sikhism considers soul (atma) to be part of God (Waheguru). Various hymns are cited from the holy book Guru Granth Sahib (SGGS) that suggests this belief. "God is in the Soul and the Soul is in the God."[86]The same concept is repeated at various pages of the SGGS. For example: "The soul is divine; divine is the soul. Worship Him with love."[87] and "The soul is the Lord, and the Lord is the soul; contemplating the Shabad, the Lord is found."[88]

The atma or soul according to Sikhism is an entity or "spiritual spark" or "light" in our body because of which the body can sustain life. On the departure of this entity from the body, the body becomes lifeless – No amount of manipulations to the body can make the person make any physical actions. The soul is the 'driver' in the body. It is theroohu or spirit or atma, the presence of which makes the physical body alive.

Many religious and philosophical traditions support the view that the soul is the ethereal substance – a spirit; a non-material spark – particular to a unique living being. Such traditions often consider the soul both immortal and innately aware of its immortal nature, as well as the true basis for sentience in each living being. The concept of the soul has strong links with notions of an afterlife, but opinions may vary wildly even within a given religion as to what happens to the soul after death. Many within these religions and philosophies see the soul as immaterial, while others consider it possibly material.

Taoism[edit]

According to Chinese traditions, every person has two types of soul called hun and po (魂 and 魄), which are respectively yang and yin.Taoism believes in ten souls, sanhunqipo (三魂七魄) "three hun and seven po".[89] A living being that loses any of them is said to have mental illness or unconsciousness, while a dead soul may reincarnateto a disability, lower desire realms, or may even be unable to reincarnate.

Zoroastrianism[edit]

Other religious beliefs and views[edit]

In theological reference to the soul, the terms "life" and "death" are viewed as emphatically more definitive than the common concepts of "biological life" and "biological death". Because the soul is said to be transcendent of thematerial existence, and is said to have (potentially)eternal life, the death of the soul is likewise said to be an eternal death. Thus, in the concept of divine judgment, God is commonly said to have options with regard to the dispensation of souls, ranging from Heaven(i.e., angels) to hell (i.e., demons), with various concepts in between. Typically both Heaven and hell are said to be eternal, or at least far beyond a typical human concept of lifespan and time.

According to Louis Ginzberg, the soul of Adam is the image of God.[90]Every soul of human also escapes from the body every night, rises up to heaven, and fetches new life thence for the body of man.[91]

Spirituality, New Age, and new religions[edit]

Dada Bhagwan[edit]

In Dada Bhagwan, The Soul is an independent eternal element. The Soul is permanent. In order to experience the Soul you need to attainSelf-Realization.[92]

Brahma Kumaris[edit]

In Brahma Kumaris, human souls are believed to be incorporeal andeternal. God is considered to be the Supreme Soul, with maximum degrees of spiritual qualities, such as peace, love and purity.[93]

Theosophy[edit]

In Helena Blavatsky's Theosophy, the soul is the field of our psychological activity (thinking, emotions, memory, desires, will, and so on) as well as of the so-called paranormal or psychic phenomena (extrasensory perception, out-of-body experiences, etc.). However, the soul is not the highest, but a middle dimension of human beings. Higher than the soul is the spirit, which is considered to be the real self; the source of everything we call "good"—happiness, wisdom, love, compassion, harmony, peace, etc. While the spirit is eternal and incorruptible, the soul is not. The soul acts as a link between the material body and the spiritual self, and therefore shares some characteristics of both. The soul can be attracted either towards the spiritual or towards the material realm, being thus the "battlefield" of good and evil. It is only when the soul is attracted towards the spiritual and merges with the Self that it becomes eternal and divine.

Anthroposophy[edit]

Rudolf Steiner claimed classical trichotomic stages of soul development, which interpenetrated one another in consciousness:[94]

- The "sentient soul", centering on sensations, drives, and passions, with strong conative (will) and emotional components;

- The "intellectual" or "mind soul", internalizing and reflecting on outer experience, with strong affective (feeling) and cognitive (thinking) components; and

- The "consciousness soul", in search of universal, objective truths.

Miscellaneous[edit]

In Surat Shabda Yoga, the soul is considered to be an exact replica and spark of the Divine. The purpose of Surat Shabd Yoga is to realize one's True Self as soul (Self-Realisation), True Essence (Spirit-Realisation) and True Divinity (God-Realisation) while living in the physical body.

Similarly, the spiritual teacher Meher Baba held that "Atma, or the soul, is in reality identical with Paramatma the Oversoul – which is one, infinite, and eternal...[and] [t]he sole purpose of creation is for the soul to enjoy the infinite state of the Oversoul consciously."[95]

Eckankar, founded by Paul Twitchell in 1965, defines Soul as the true self; the inner, most sacred part of each person.[96]

Philosophical views[edit]

The ancient Greeks used the word "ensouled" to represent the concept of being "alive", indicating that the earliest surviving western philosophical view believed that the soul was that which gave the body life.[97] The soul was considered the incorporeal or spiritual "breath" that animates (from the Latin, anima, cf. "animal") the living organism.

Francis M. Cornford quotes Pindar by saying that the soul sleeps while the limbs are active, but when one is sleeping, the soul is active and reveals "an award of joy or sorrow drawing near" in dreams.[98]

Erwin Rohde writes that an early pre-Pythagorean belief presented the soul as lifeless when it departed the body, and that it retired intoHades with no hope of returning to a body.[99]

Socrates and Plato[edit]

Drawing on the words of his teacher Socrates, Plato considered the psyche to be the essence of a person, being that which decides how we behave. He considered this essence to be an incorporeal, eternal occupant of our being. Plato said that even after death, the soul exists and is able to think. He believed that as bodies die, the soul is continually reborn (metempsychosis) in subsequent bodies. However, Aristotle believed that only one part of the soul was immortal namely the intellect (logos). The Platonic soul consists of three parts:[100]

- the logos, or logistikon (mind, nous, or reason)

- the thymos, or thumetikon (emotion, spiritedness, or masculine)

- the eros, or epithumetikon (appetitive, desire, or feminine)

The parts are located in different regions of the body:

- logos is located in the head, is related to reason and regulates the other part.

- thymos is located near the chest region and is related to anger.

- eros is located in the stomach and is related to one's desires.

Plato also compares the three parts of the soul or psyche to a societalcaste system. According to Plato's theory, the three-part soul is essentially the same thing as a state's class system because, to function well, each part must contribute so that the whole functions well. Logos keeps the other functions of the soul regulated.

Aristotle[edit]

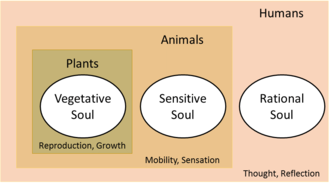

Aristotle (384–322 BCE) defined the soul, or Psūchê (ψυχή), as the "first actuality" of a naturally organized body,[101] and argued against its separate existence from the physical body. In Aristotle's view, the primary activity, or full actualization, of a living thing constitutes its soul. For example, the full actualization of an eye, as an independent organism, is to see (its purpose or final cause).[102] Another example is that the full actualization of a human being would be living a fully functional human life in accordance with reason (which he considered to be a faculty unique to humanity).[103] For Aristotle, the soul is the organization of the form and matter of a natural being which allows it to strive for its full actualization. This organization between form and matter is necessary for any activity, or functionality, to be possible in a natural being. Using an artifact (non-natural being) as an example, a house is a building for human habituation, but for a house to be actualized requires the material (wood, nails, bricks, etc.) necessary for its actuality (i.e. being a fully functional house). However, this does not imply that a house has a soul. In regards to artifacts, the source of motion that is required for their full actualization is outside of themselves (for example, a builder builds a house). In natural beings, this source of motion is contained within the being itself.[104]Aristotle elaborates on this point when he addresses the faculties of the soul.

The various faculties of the soul, such as nutrition, movement (peculiar to animals), reason (peculiar to humans), sensation (special, common, and incidental) and so forth, when exercised, constitute the "second" actuality, or fulfillment, of the capacity to be alive. For example, someone who falls asleep, as opposed to someone who falls dead, can wake up and live their life, while the latter can no longer do so.

Aristotle identified three hierarchical levels of natural beings: plants, animals, and people, having three different degrees of soul: Bios(life), Zoë (animate life), and Psuchë (self-conscious life). For these groups, he identified three corresponding levels of soul, or biological activity: the nutritive activity of growth, sustenance and reproduction which all life shares (Bios); the self-willed motive activity and sensory faculties, which only animals and people have in common (Zoë); and finally "reason", of which people alone are capable (Pseuchë).

Aristotle's discussion of the soul is in his work, De Anima (On the Soul). Although mostly seen as opposing Plato in regard to the immortality of the soul, a controversy can be found in relation to the fifth chapter of the third book: In this text both interpretations can be argued for, soul as a whole can be deemed mortal, and a part called "active intellect" or "active mind" is immortal and eternal.[105]Advocates exist for both sides of the controversy, but it has been understood that there will be permanent disagreement about its final conclusions, as no other Aristotelian text contains this specific point, and this part of De Anima is obscure.[106] Further, Aristotle states that the soul helps humans find the truth and understanding the true purpose or role of the soul is extremely difficult.[107]

Avicenna and Ibn al-Nafis[edit]

Following Aristotle, Avicenna (Ibn Sina) and Ibn al-Nafis, an Arab physician, further elaborated upon the Aristotelian understanding of the soul and developed their own theories on the soul. They both made a distinction between the soul and the spirit, and the Avicenniandoctrine on the nature of the soul was influential among theScholastics. Some of Avicenna's views on the soul include the idea that the immortality of the soul is a consequence of its nature, and not a purpose for it to fulfill. In his theory of "The Ten Intellects", he viewed the human soul as the tenth and final intellect.[108][109]

While he was imprisoned, Avicenna wrote his famous "Floating Man"thought experiment to demonstrate human self-awareness and the substantial nature of the soul.[110] He told his readers to imagine themselves suspended in the air, isolated from all sensations, which includes no sensory contact with even their own bodies. He argues that in this scenario one would still have self-consciousness. He thus concludes that the idea of the self is not logically dependent on any physical thing, and that the soul should not be seen in relative terms, but as a primary given, a substance. This argument was later refined and simplified by René Descartes in epistemic terms, when he stated: "I can abstract from the supposition of all external things, but not from the supposition of my own consciousness."[111]

Avicenna generally supported Aristotle's idea of the soul originating from the heart, whereas Ibn al-Nafis rejected this idea and instead argued that the soul "is related to the entirety and not to one or a feworgans". He further criticized Aristotle's idea whereby every unique soul requires the existence of a unique source, in this case the heart. al-Nafis concluded that "the soul is related primarily neither to the spirit nor to any organ, but rather to the entire matter whose temperament is prepared to receive that soul," and he defined the soul as nothing other than "what a human indicates by saying "I".[112]

Thomas Aquinas[edit]

Following Aristotle (whom he referred to as "the Philosopher") and Avicenna, Thomas Aquinas (1225–74) understood the soul to be the first actuality of the living body. Consequent to this, he distinguished three orders of life: plants, which feed and grow; animals, which add sensation to the operations of plants; and humans, which add intellect to the operations of animals.

Concerning the human soul, his epistemological theory required that, since the knower becomes what he knows, the soul is definitely not corporeal—if it is corporeal when it knows what some corporeal thing is, that thing would come to be within it.[113] Therefore, the soul has an operation which does not rely on a body organ, and therefore the soul can exist without a body. Furthermore, since the rational soul of human beings is a subsistent form and not something made of matter and form, it cannot be destroyed in any natural process.[114] The full argument for the immortality of the soul and Aquinas' elaboration of Aristotelian theory is found in Question 75 of the First Part of theSumma Theologica.

Immanuel Kant[edit]

In his discussions of rational psychology, Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) identified the soul as the "I" in the strictest sense, and argued that the existence of inner experience can neither be proved nor disproved.

It is from the "I", or soul, that Kant proposes transcendental rationalization, but cautions that such rationalization can only determine the limits of knowledge if it is to remain practical.[115]

Philosophy of mind[edit]

Gilbert Ryle's ghost in the machine argument, which is a rejection of Descartes' mind–body dualism, can provide a contemporary understanding of the soul/mind, and the problem concerning its connection to the brain/body.[116]

James Hillman[edit]

Psychologist James Hillman's archetypal psychology is an attempt to restore the concept of the soul, which Hillman viewed as the "self-sustaining and imagining substrate" upon which consciousness rests. Hillman described the soul as that "which makes meaning possible, [deepens] events into experiences, is communicated in love, and has a religious concern", as well as "a special relation with death".[117]Departing from the Cartesian dualism "between outer tangible reality and inner states of mind", Hillman takes the Neoplatonic stance[118]that there is a "third, middle position" in which soul resides.[119]Archetypal psychology acknowledges this third position by attuning to, and often accepting, the archetypes, dreams, myths, and evenpsychopathologies through which, in Hillman's view, soul expresses itself.

Science[edit]

Many modern scientists, such as Julien Musolino, hold that the mind is merely a complex machine that operates on the same physical laws as all other objects in the universe.[120] According to Musolino, there is currently no scientific evidence whatsoever to support the existence of the soul;[120] he claims there is also considerable evidence that seems to indicate that souls do not exist.[120]

The search for the soul, however, is seen to have been instrumental in driving the understanding of the anatomy and physiology of the human body, particularly in the fields of cardiovascular and neurology.[121] In the two dominant conflicting concepts of the soul – one seeing it to be spiritual and immortal, and the other seeing it to be material and mortal, both have described the soul as being located in a particular organ or as pervading the whole body.[121]

Neuroscience[edit]

Neuroscience as an interdisciplinary field, and its branch of cognitive neuroscience particularly, operates under the ontological assumption of physicalism. In other words, it assumes—in order to perform its science—that only the fundamental phenomena studied by physicsexist. Thus, neuroscience seeks to understand mental phenomena within the framework according to which human thought and behaviorare caused solely by physical processes taking place inside the brain, and it operates by the way of reductionism by seeking an explanation for the mind in terms of brain activity.[122][123]

To study the mind in terms of the brain several methods of functional neuroimaging are used to study the neuroanatomical correlates of various cognitive processes that constitute the mind. The evidence from brain imaging indicates that all processes of the mind have physical correlates in brain function.[124] However, such correlational studies cannot determine whether neural activity plays a causal role in the occurrence of these cognitive processes (correlation does not imply causation) and they cannot determine if the neural activity is either necessary or sufficient for such processes to occur. Identification of causation, and of necessary and sufficient conditions requires explicit experimental manipulation of that activity. If manipulation of brain activity changes consciousness, then a causal role for that brain activity can be inferred.[125][126] Two of the most common types of manipulation experiments are loss-of-function and gain-of-function experiments. In a loss-of-function (also called "necessity") experiment, a part of the nervous system is diminished or removed in an attempt to determine if it is necessary for a certain process to occur, and in a gain-of-function (also called "sufficiency") experiment, an aspect of the nervous system is increased relative to normal.[127] Manipulations of brain activity can be performed with direct electrical brain stimulation, magnetic brain stimulation usingtranscranial magnetic stimulation, psychopharmacologicalmanipulation, optogenetic manipulation, and by studying the symptoms of brain damage (case studies) and lesions. In addition, neuroscientists are also investigating how the mind develops with the development of the brain.[128]

Physics[edit]

Physicist Sean M. Carroll has written that the idea of a soul is incompatible with quantum field theory (QFT). He writes that for a soul to exist: "Not only is new physics required, but dramatically new physics. Within QFT, there can't be a new collection of 'spirit particles' and 'spirit forces' that interact with our regular atoms, because we would have detected them in existing experiments."[129]

Some[quantify] theorists have invoked quantum indeterminism as an explanatory mechanism for possible soul/brain interaction, but neuroscientist Peter Clarke found errors with this viewpoint, noting there is no evidence that such processes play a role in brain function; Clarke concluded that a Cartesian soul has no basis from quantum physics.[130][need quotation to verify]

Parapsychology[edit]

Some parapsychologists have attempted to establish, by scientificexperiment, whether a soul separate from the brain exists, as is more commonly defined in religion rather than as a synonym of psyche or mind. Milbourne Christopher (1979) and Mary Roach (2010) have argued that none of the attempts by parapsychologists have yet succeeded.[131][132]

Weight of the soul[edit]

In 1901 Duncan MacDougall conducted an experiment in which he made weight measurements of patients as they died. He claimed that there was weight loss of varying amounts at the time of death; he concluded the soul weighed 21 grams, based on measurements of a single patient and discarding conflicting results.[133][134] The physicistRobert L. Park has written that MacDougall's experiments "are not regarded today as having any scientific merit" and the psychologistBruce Hood wrote that "because the weight loss was not reliable or replicable, his findings were unscientific."[135][136]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ "soul."Encyclopædia Britannica. 2010. Encyclopædia Britannica 2006 CD. 13 July 2010.

- ^ "Soul (noun)". Oxford English Dictionary (OED) online edition. Oxford English Dictionary (OED). Retrieved 1 December2016.

- ^ "Immortality of the Soul". www.jewishencyclopedia.com.Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- ^ Peter Eardley and Carl Still, Aquinas: A Guide for the Perplexed (London: Continuum, 2010), pp. 34–35

- ^ "Soul", The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition. 2001–07. Retrieved 12 November 2008.

- ^ "Found: An Ancient Monument to the Soul". The New York Times. 17 November 2008. Archived from the original on 24 April 2009. Retrieved 18 November 2008. In a mountainous kingdom in what is now southeastern Turkey, there lived in the eighth century B.C. a royal official, Kuttamuwa, who oversaw the completion of an inscribed stone monument, or stele, to be erected upon his death. The words instructed mourners to commemorate his life and afterlife with feasts "for my soul that is in this stele."

- ^ Bahá'u'lláh (1976). Gleanings from the Writings of Bahá'u'lláh. Wilmette, Illinois: Bahá'í Publishing Trust. pp. 158–63. ISBN 978-0-87743-187-9 . Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- ^ Bahá'u'lláh (1976). Gleanings from the Writings of Bahá'u'lláh. Wilmette, Illinois: Bahá'í Publishing Trust. pp. 155–58. ISBN 978-0-87743-187-9 . Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- ^ a b Taherzadeh, Adib (1976). The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh, Volume 1. Oxford: George Ronald. ISBN 978-0-85398-270-8 .Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- ^ Walpola Rahula, What the Buddha Taught (NY: Grove, 1962), p. 25

- ^ Sources of Indian Tradition, vol. 1, ed. Theodore de Bary (NY: Columbia UP, 1958), pp. 92–93

- ^ Walpola Rahula, What the Buddha Taught (NY: Grove, 1962), pp. 55–57

- ^ Sources of Indian Tradition, vol. 1, ed. Theodore de Bary (NY: Columbia UP, 1958), p. 93

- ^ Walpola Rahula, What the Buddha Taught (NY: Grove, 1962), p. 55

- ^ Sources of Indian Tradition, vol. 1, ed. Theodore de Bary (NY: Columbia UP, 1958), pp. 93–94

- ^ for example, in Walpola Rahula, What the Buddha Taught(NY: Grove, 1962), pp. 51–66

- ^ a b Sources of Indian Tradition, vol. 1, ed. Theodore de Bary (NY: Columbia UP, 1958), p. 94

- ^ Walpola Rahula, What the Buddha Taught (NY: Grove, 1962), p. 26

- ^ Walpola Rahula, What the Buddha Taught (NY: Grove, 1962), p. 34

- ^ Walpola Rahula, What the Buddha Taught (NY: Grove, 1962), p. 33

- ^ Conze, Edward (1993). A Short History of Buddhism. Oneworld. p. 14. ISBN 978-1-85168-066-5 .

- ^ Walpola Rahula, What the Buddha Taught (NY: Grove, 1962), p. 51

- ^ "六朝神滅不滅論與佛教輪迴主體之研究". Ccbs.ntu.edu.tw. Archived from the original on 13 March 2012. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- ^ "佛教心理論之發達觀". Ccbs.ntu.edu.tw. Archived from the original on 13 March 2012. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- ^ "植物、草木、山石是无情众生吗?有佛性吗?". Bskk.com. Archived from the original on 9 October 2011. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- ^ "從律典探索佛教對動物的態度(中)". Awker.com. Archived from the original on 21 November 2011. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- ^ "無情眾生現今是不具有神識,但具有佛性!". Dharma.com.tw. Archived from the original on 30 December 2011. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- ^ 无情有佛性

- ^ B. Alan Wallace, Contemplative Science. University of Columbia Press, 2007, p. 13.

- ^ Smith, Joseph (1981). Doctrine and Covenants. Salt Lake City, Utah: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints. p. 286. ISBN 978-1-59297-503-7 .

- ^ ""Do Embryos Have Souls?", Father Tadeusz Pacholczyk, PhD, Catholic Education Resource Center". Catholiceducation.org. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- ^ Matthew Syed (12 May 2008). "Embryos have souls? What nonsense". The Times. UK. Archived from the original on 18 September 2011. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- ^ "The Soul of the Embryo: An Enquiry into the Status of the Human Embryo in the Christian Tradition", by David Albert Jones, Continuum Press, 2005, ISBN 978-0-8264-6296-1

- ^ "Soul". newadvent.org. 1 July 1912. Archived from the original on 28 November 2011. Retrieved 13 November 2011. In St. Paul we find a more technical phraseology employed with great consistency. Psyche is now appropriated to the purely natural life; pneuma to the life of supernatural religion, the principle of which is the Holy Spirit, dwelling and operating in the heart. The opposition of flesh and spirit is accentuated afresh (Romans 1:18, etc.). This Pauline system, presented to a world already prepossessed in favour of a quasi-Platonic Dualism, occasioned one of the earliest widespread forms of error among Christian writers – the doctrine of the Trichotomy. According to this, man, perfect man (teleios) consists of three parts: body, soul, spirit (soma, psyche, pneuma).

- ^ "Catechism of the Catholic Church, paragraph 363". Vatican.va. Archived from the original on 16 November 2011. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- ^ "Catechism of the Catholic Church, paragraph 382". Vatican.va. Archived from the original on 16 November 2011. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- ^ Paul Helm, John Calvin's Ideas 2006 p. 129 "The Immortality of the Soul: As we saw when discussing Calvin's Christology, Calvin is a substance dualist."

- ^ Anthony Grafton, Glenn W. Most, Salvatore Settis The Classical Tradition 2010 p. 480 "On several occasions, Luther mentioned contemptuously that the Council Fathers had decreed the soul immortal."

- ^ Richard Marius Martin Luther: the Christian between God and death 1999 p. 429 "Luther, believing in soul sleep at death, held here that in the moment of resurrection... the righteous will rise to meet Christ in the air, the ungodly will remain on earth for judgment,..."

- ^ Birmingham Amended Statement of Faith. Available onlineArchived 16 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Do You Have an Immortal Soul?". The Watchtower: 3–5. 15 July 2007. Archived from the original on 31 December 2014.

- ^ What Does the Bible Really Teach?. p. 211.

- ^ [Doctrine & Covenants of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City, Utah; 88:15]https://books.google.com/books?id=Err_Jdbuu84C = "And the spirit and the body is the soul of man."

- ^ "Moses 6:51". churchofjesuschrist.org. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- ^ "Hebrews 12:9". churchofjesuschrist.org. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- ^ Joseph Smith goes so far as to say that these spirits are made of a finer matter that we cannot see in our current state: Doctrine and Covenants 131:7–8

- ^ Book of Mormon. Alma: 5:15; 11:43–45; 40:23; 41:2

- ^ Doctrine and Covenants 93:33–34https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/scriptures/dc-testament/dc/93.33-34?lang=eng [1]

- ^ Doctrine and Covenants 93:29–30https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/scriptures/dc-testament/dc/93.29-30?lang=eng [2]

- ^ Chapter 37, Teachings of Presidents of the Church: Joseph F. Smith, (2011), 331–38

- ^ "Spirit." Guide to the Scriptures "Spirit". Retrieved 7 April2014.

- ^ "Gospel Principles Chapter 41: The Postmortal Spirit World".churchofjesuschrist.org. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- ^ Boot, W.J. (2014). "3: Spirits, Gods and Heaven in Confucian thought". In Huang, Chun-chieh; Tucker, John Allen (eds.). Dao Companion to Japanese Confucian Philosophy. Dao Companions to Chinese Philosophy. 5. Dordrecht: Springer. p. 83. ISBN 9789048129218 . Retrieved 27 April 2019. [...] Confucius combines qi with the divine and the essential, and the corporeal soul with ghosts, opposes the two (as yang against yin, spiritual soul against corporal soul) andd explains that after death the first will rise up, and the second will return to the earth, while the flesh and bones will disintegrate.

- ^ [a] Atman Archived 23 December 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Oxford Dictionaries, Oxford University Press (2012),Quote: "1. real self of the individual; 2. a person's soul";

[b] John Bowker (2000), The Concise Oxford Dictionary of World Religions, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-280094-7, See entry for Atman;

[c] WJ Johnson (2009), A Dictionary of Hinduism, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-861025-0, See entry for Atman (self). - ^ a b David Lorenzen (2004), The Hindu World (Editors: Sushil Mittal and Gene Thursby), Routledge, ISBN 0-415-21527-7, pp. 208–09, Quote: "Advaita and nirguni movements, on the other hand, stress an interior mysticism in which the devotee seeks to discover the identity of individual soul (atman) with the universal ground of being (brahman) or to find god within himself".

- ^ Chad Meister (2010), The Oxford Handbook of Religious Diversity, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-534013-6, p. 63; Quote: "Even though Buddhism explicitly rejected the Hindu ideas of Atman ("soul") and Brahman, Hinduism treats Sakyamuni Buddha as one of the ten avatars of Vishnu."

- ^ Deussen, Paul and Geden, A.S. The Philosophy of the Upanishads. Cosimo Classics (1 June 2010). p. 86. ISBN 1-61640-240-7.

- ^ Richard King (1995), Early Advaita Vedanta and Buddhism, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0-7914-2513-8, p. 64, Quote: "Atman as the innermost essence or soul of man, and Brahman as the innermost essence and support of the universe. (...) Thus we can see in the Upanishads, a tendency towards a convergence of microcosm and macrocosm, culminating in the equating of atman with Brahman".

- ^ KN Jayatilleke (2010), Early Buddhist Theory of Knowledge,ISBN 978-81-208-0619-1, pp. 246–49, from note 385 onwards; Steven Collins (1994), Religion and Practical Reason (Editors: Frank Reynolds, David Tracy), State Univ of New York Press,ISBN 978-0-7914-2217-5, p. 64; "Central to Buddhist soteriology is the doctrine of not-self (Pali: anattā, Sanskrit: anātman, the opposed doctrine of ātman is central to Brahmanical thought). Put very briefly, this is the [Buddhist] doctrine that human beings have no soul, no self, no unchanging essence."; Edward Roer (Translator), Shankara's Introduction, p. 2, at Google Books to Brihad Aranyaka Upanishad, pp. 2–4; Katie Javanaud (2013), Is The Buddhist ‘No-Self’ Doctrine Compatible With Pursuing Nirvana? Archived6 February 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Philosophy Now

- ^ Matthew Hall (2011). Plants as Persons: A Philosophical Botany. State University of New York Press. p. 76. ISBN 978-1-4384-3430-8 .

- ^ a b J Jaini (1940). Outlines of Jainism. Cambridge University Press. pp. xxii–xxiii.

- ^ Jaini, Jagmandar-lāl (1927), Gommatsara Jiva-kanda, p. 54Alt URL

- ^ Sarao, K.T.S.; Long, Jeffery D., eds. (2017). "Jīva (Jainism)". Buddhism and Jainism. Encyclopedia of Indian Religions. Springer Netherlands. p. 594. doi:10.1007/978-94-024-0852-2_100397. ISBN 978-94-024-0851-5 .

- ^ a b Jean Varenne (1989). Yoga and the Hindu Tradition. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 45–47. ISBN 978-81-208-0543-9 .

- ^ Michael Myers (2013). Brahman: A Comparative Theology. Routledge. pp. 140–43. ISBN 978-1-136-83565-0 .

- ^ The Philosophy of Person: Solidarity and Cultural Creativity, Jozef Tischner and George McClean, 1994, p. 32

- ^ Deuraseh, Nurdeen; Abu Talib, Mansor (2005). "Mental health in Islamic medical tradition". The International Medical Journal. 4 (2): 76–79.

- ^ Bragazzi, NL; Khabbache, H (2018). "Neurotheology of Islam and Higher Consciousness States". Cosmos and History: The Journal of Natural and Social Philosophy. 14 (2): 315–21.

- ^ Ahmad, Sultan (2011). "Nafs: What Is it?". Islam in Perspective (revised ed.). Author House. p. 180. ISBN 978-1-4490-3993-6 . Retrieved 15 July 2017 – via Google Books.

- ^ Sangave, Vilas Adinath (2001). Aspects of Jaina religion (3 ed.). Bharatiya Jnanpith. pp. 15–16. ISBN 81-263-0626-2 .

- ^ "Forgotten Gandhi, Virchand Gandhi (1864–1901) – Advocate of Universal Brotherhood". All Famous Quotes. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013.

- ^ Zohar, Rayah Mehemna, Terumah 158b. See Leibowitz, Aryeh (2018). The Neshamah: A Study of the Human Soul. Feldheim Publishers. pp. 27, 110. ISBN 1-68025-338-7

- ^ The only person mentioned in the Torah celebrating birthday (party) is the wicked pharaoh of Egypt Genesis 40:20–22.

- ^ HaQoton, Reb Chaim (17 April 2007). "Happy Birthday". Reb Chaim HaQoton. Archived from the original on 9 November 2013. Retrieved 11 July 2013.

- ^ "About Jewish Birthdays". Judaism 101. Aish.com. Archivedfrom the original on 22 August 2013. Retrieved 11 July 2013.

- ^ "Soul". jewishencyclopedia.com. Archived from the original on 8 March 2016.

- ^ a b Tan, Michael L. (2008). Revisiting Usog, Pasma, Kulam. University of the Philippines Press. ISBN 9789715425704 .

- ^ Clifford Sather (2018). "A work of love: Awareness and expressions of emotion in a Borneo healing ritual". In James J. Fox (ed.). Expressions of Austronesian Thought and Emotions. ANU Press. pp. 57–63. ISBN 9781760461928 .

- ^ Yu, Jose Vidamor B. (2000). Inculturation of Filipino-Chinese Culture Mentality. Interreligious and Intercultural Investigations. 3. Editrice Pontifica Universita Gregoriana. pp. 148–149. ISBN 9788876528484 .

- ^ Robert Blust; Stephen Trussel. "*du". Austronesian Comparative Dictionary. Retrieved 7 July 2018.

- ^ Leonardo N. Mercado (1991). "Soul and Spirit in Filipino Thought". Philippine Studies. 39 (3): 287–302.JSTOR 42633258.

- ^ Zeus A. Salazar (2007). "Faith healing in the Philippines: An historical perspective" (PDF). Asian Studies. 43 (2v): 1–15.

- ^ Kleivan & Sonne (1985) pp. 17–18

- ^ Merkur (1985) pp. 61, 222–223, 226, 240

- ^ Gabus (1970) p. 211

- ^ SGGS, M 1, p. 1153.

- ^ SGGS, M 4, p. 1325.

- ^ SGGS, M 1, p. 1030.

- ^ "Encyclopedia of Death and Dying (2008)". Deathreference.com. Archived from the original on 5 November 2011. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- ^ Ginzberg, Louis (1909). The Legends of the Jews Vol I, Chapter II: Adam Archived 1 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine (Translated by Henrietta Szold) Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society.

Citation: God had fashioned his (Adam's) soul with particular care. She is the image of God, and as God fills the world, so the soul fills the human body; as God sees all things, and is seen by none, so the soul sees, but cannot be seen; as God guides the world, so the soul guides the body; as God in His holiness is pure, so is the soul; and as God dwells in secret, so doth the soul. - ^ Ginzberg, Louis (1909). The Legends of the Jews Vol I, Chapter II: The Soul of Man Archived 1 December 2017 at theWayback Machine (Translated by Henrietta Szold) Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society.

- ^ "Spiritual Awakening | Signs of Spiritual Awakening | Spiritual Awakening Symptoms | Spiritual Experience".

- ^ Ramsay, Tamasin (September 2010). "Custodians of Purity An Ethnography of the Brahma Kumaris". Monash University: 105.

- ^ Creeger, Rudolf Steiner; translated by Catherine E. (1994).Theosophy: an introduction to the spiritual processes in human life and in the cosmos (3rd ed.). Hudson, NY: Anthroposophic Press. pp. 42–46. ISBN 978-0-88010-373-2 .

- ^ Baba, Meher. (1987). Discourses. Myrtle Beach, SC: Sheriar Press. p. 222. ISBN 978-1-880619-09-4.

- ^ Klemp, H. (2009). The call of soul. Minneapolis, MN: Eckankar

- ^ Lorenz, Hendrik (2009). Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2009 ed.). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University.

- ^ Francis M. Cornford, Greek Religious Thought, p. 64, referring to Pindar, Fragment 131.

- ^ Erwin Rohde, Psyche, 1928.

- ^ Jones, David (2009). The Gift of Logos: Essays in Continental Philosophy. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 33–35. ISBN 978-1-4438-1825-4 . Retrieved 23 February2016.

- ^ Aristotle. On The Soul. p. 412b5.

- ^ Aristotle. Physics. Book VIII, Chapter 5, pp. 256a5–22.

- ^ Aristotle. Nicomachean Ethics. Book I, Chapter 7, pp. 1098a7–17.

- ^ Aristotle. Physics. Book III, Chapter 1, pp. 201a10–25.

- ^ Aristotle. On The Soul. Book III, Chapter 5, pp. 430a24–25.

- ^ Shields, Christopher (2011). "supplement: The Active Mind of De Anima iii 5)". Aristotle's Psychology. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 12 December 2013.

- ^ Smith, J. S. (Trans) (1973). Introduction to Aristotle. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 155–59.

- ^ Nahyan A.G. Fancy (2006), "Pulmonary Transit and Bodily Resurrection: The Interaction of Medicine, Philosophy and Religion in the Works of Ibn al-Nafīs (d. 1288)", pp. 209–10 (Electronic Theses and Dissertations, University of Notre Dame).

- ^ "Arabic and Islamic Psychology and Philosophy of Mind".Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 29 May 2012.

- ^ "Floating Man – The Art and Popular Culture Encyclopedia".www.artandpopularculture.com. Archived from the original on 26 April 2018. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- ^ Seyyed Hossein Nasr and Oliver Leaman (1996), History of Islamic Philosophy, p. 315, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-13159-6.

- ^ Nahyan A.G. Fancy (2006). Pulmonary Transit and Bodily Resurrection: The Interaction of Medicine, Philosophy and Religion in the Works of Ibn al-Nafīs (d. 1288). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, University of Notre Dame (Thesis). University of Notre Dame. pp. 209–210. Archived from the original on 4 April 2015.

- ^ Aquinas, Thomas. "Quaestiones Disputatae de Veritate" (in Latin). Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved23 February 2016.

- ^ Aquinas, Thomas. "Super Boetium De Trinitate" (in Latin).Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- ^ Bishop, Paul (2000). Synchronicity and Intellectual Intuition in Kant, Swedenborg, and Jung. US: The Edwin Mellen Press. pp. 262–67. ISBN 978-0-7734-7593-9 .

- ^ Ryle, Gilbert (1949). The Concept of Mind. University of Chicago Press.

- ^ Hillman J (T Moore, Ed.) (1989). A blue fire: Selected writings by James Hillman. New York: HarperPerennial. p. 21.

- ^ Hillman J (T Moore, Ed.) (1989). A blue fire: Selected writings by James Hillman. New York: HarperPerennial. p. 112.

- ^ Hillman J (T Moore, Ed.) (1989). A blue fire: Selected writings by James Hillman. New York: HarperPerennial. p. 121.

- ^ a b c Musolino, Julien (2015). The Soul Fallacy: What Science Shows We Gain from Letting Go of Our Soul Beliefs. Amherst, New York: Prometheus Books. pp. 21–38. ISBN 978-1-61614-962-8 .

- ^ a b Santoro, G; Wood, MD; Merlo, L; Anastasi, GP; Tomasello, F; Germanò, A (October 2009). "The anatomic location of the soul from the heart, through the brain, to the whole body, and beyond: a journey through Western history, science, and philosophy". Neurosurgery. 65 (4): 633–43, discussion 643. doi:10.1227/01.NEU.0000349750.22332.6A.PMID 19834368.

- ^ O. Carter Snead. "Cognitive Neuroscience and the Future of Punishment Archived 5 November 2014 at the Wayback Machine" (2010).

- ^ Kandel, ER; Schwartz JH; Jessell TM; Siegelbaum SA; Hudspeth AJ. "Principles of Neural Science, Fifth Edition" (2012).

- ^ Andrea Eugenio Cavanna, Andrea Nani, Hal Blumenfeld, Steven Laureys. "Neuroimaging of Consciousness" (2013).

- ^ Farah, Martha J.; Murphy, Nancey (February 2009). "Neuroscience and the Soul". Science. 323 (5918): 1168.doi:10.1126/science.323.5918.1168a. PMID 19251609.

- ^ Max Velmans, Susan Schneider. "The Blackwell Companion to Consciousness" (2008). p. 560.

- ^ Matt Carter, Jennifer C. Shieh. "Guide to Research Techniques in Neuroscience" (2009).

- ^ Squire, L. et al. "Fundamental Neuroscience, 4th edition" (2012). Chapter 43.

- ^ Carroll, Sean M.. (2011). "Physics and the Immortality of the Soul" Archived 6 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine.Scientific American. Retrieved 2014-10-11.

- ^ Clarke, Peter. (2014). Neuroscience, Quantum Indeterminism and the Cartesian Soul Archived 10 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Brain and cognition 84: 109–17.

- ^ Milbourne Christopher. (1979). Search for the Soul: An Insider's Report on the Continuing Quest by Psychics and Scientists for Evidence of Life After Death. Thomas Y. Crowell, Publishers.

- ^ Mary Roach. (2010). Spook: Science Tackles the Afterlife. Canongate Books Ltd. ISBN 978-1-84767-080-9

- ^ MacDougall, Duncan (1907). "The Soul: Hypothesis Concerning Soul Substance Together with Experimental Evidence of the Existence of Such Substance". American Medicine. New Series. 2: 240–43.

- ^ "How much does the soul weights?". Archived from the original on 28 April 2016.

- ^ Park, Robert L. (2009). Superstition: Belief in the Age of Science. Princeton University Press. p. 90. ISBN 978-0-691-13355-3

- ^ Hood, Bruce. (2009). Supersense: From Superstition to Religion – The Brain Science of Belief. Constable. p. 165.ISBN 978-1-84901-030-6

.